Virginia City, Nevada's Film History [Episode 1]

A serialized look at the largest silver mining region in the world's spotlight on "the Silver Screen", from the early & Silent Film era to today.

Prelude

When Virginia City, Nevada was the silver mining capital of the world during the 1860s and 1870s, Hollywood was still decades away from being a twinkle in Tinseltown’s eye.

Virginia City and the surrounding towns that make up the historic Comstock Lode mining region of Northern Nevada (including Gold Hill, Silver City, and Dayton), had an estimated population of 25,000 in those decades.

“Hollywood” as we know it, didn’t yet exist and Los Angeles was a largely agricultural region at the time with a population of about 4,385 people. The fathers of American filmmaking hadn’t yet even begun to court, let alone conceive of this new industry that would become America’s major export to the world in the coming centuries.

At the time of the discovery of Nevada’s Comstock Lode silver strike, it was silver ore, not the Silver Screen, that served as a fortune and fate-changing catalyst on the national and international stage. As a direct result of the silver mines in Virginia City and the Comstock mining region of the 1860s & 1870s, the world changed as we knew it.

A few ‘miner’ occurrences as a result of the doin’s in Virginia City during these two decades include: the United States passed the Emancipation Proclimation, Europe ended the use Silver Standard for their currency, Levi Strauss jeans were invented and Frank Sinatra recorded Irving Berlin’s romantic anthem, “Always”.

(So did Ella Fitzgerald, Paul McCartney, Bing Crosby, Patsy Cline, Judy Garland, Willie Nelson, Leonard Cohen, and so on…)

Irving Berlin (a movie score maestro in his own right) wrote ‘Always’ as a wedding present to his wife, Ellin (Mackay) Berlin. Ellin Mackay was the granddaughter of Virginia City “Bonanza King” John Mackay, who found his fortune and his wife, Mary Louise (Ellin’s grandmother), in Virginia City.

America’s major exports would eventually shift from silver in the purest quality and the vastest quantity the world had ever seen, to other goods and services. The reasons for this are longer than an article on film history needs, but we’ll address them here on this site over time.

Right around the comparative decline of silver mining in Northern Nevada, a new industry was just about to emerge in America, this time centered in New Jersey. It would go on to be one of America’s most influential and profitable industries: filmmaking.

The miners and mining barons who established their financial dynasties rooted in the rich soil of the Comstock would eventually cash in their silver chips in the region and stake claims elsewhere: among them were San Francisco, New York, Paris, and a slowly blossoming city called Los Angeles.

The formation of early Hollywood has a Comstock influence. And, several decades later, Hollywood returned the favor to Virginia City (which we’ll explore in a future installment). This collection of ranchos in Southern California that would go on to become Los Angeles, began to see a similar influx of population, commerce, ingenuity, and international attention the Comstock experienced some 40-50 years prior.

Several prospectors who found their fortunes in Virginia City & the Comstock’s rich soil pulled up stakes from Northern Nevada and sought to spend or bet their silver chips at other tables. Some bought in to the new bet of Los Angeles, California.

Lucky Baldwin.

Later, the Santa Anita Race Track became a playground for Hollywood’s A-List.

William Randolph Hearst—the infamous newspaper baron who inspired Citizen Kane and dated Hollywood star Marion Davies—owes the seeds for his family’s fortune to his father George Hearst, who first found fortune in Virginia City with the Ophir Mine.

Moving Pictures

But Virginia City’s connection with filmmaking predates even these events.

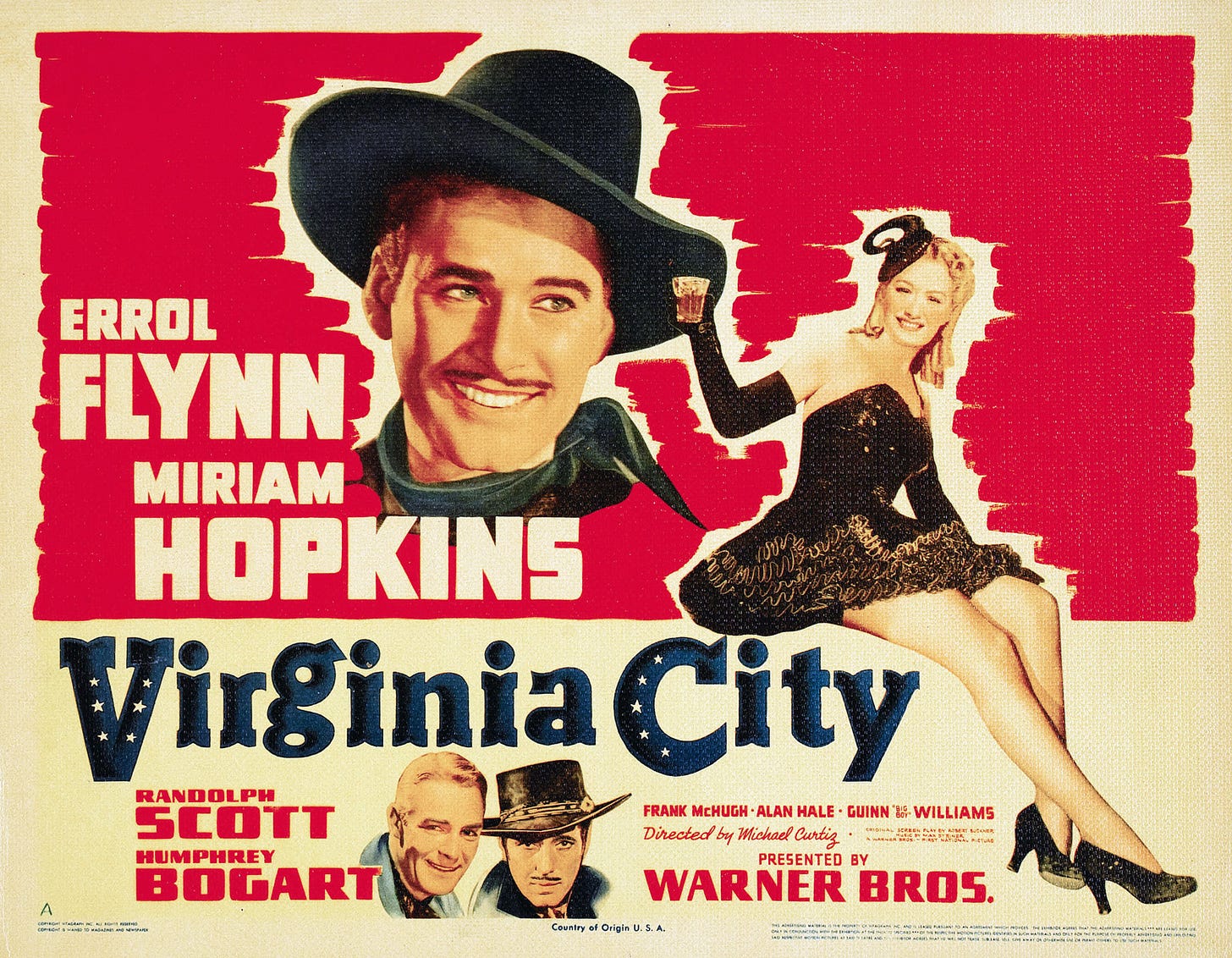

Many a “Film Studies 101” course will feature “The Horse in Motion”, the first stop-motion film, created by English photographer and film pioneer Eadweard Muybridge in 1878. But before Muybridge created what is widely regarded as the first “moving picture”—that is to say, the first “movie”—Eadweard was a still photographer.

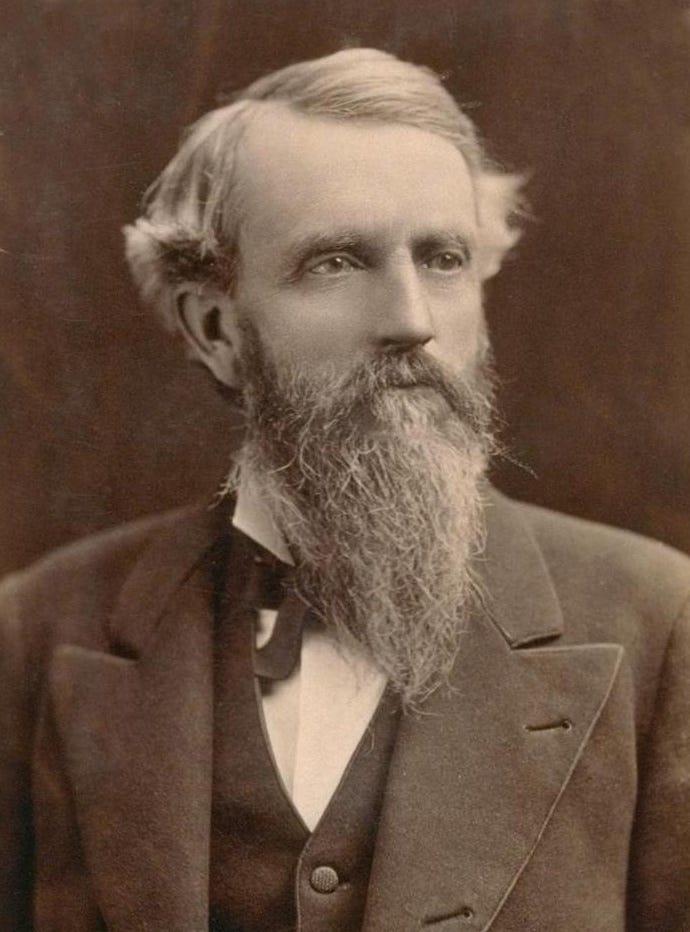

He visited the Comstock mining region (then known as Washoe)—which includes Virginia City, Gold Hill, Silver City and Dayton, Nevada—circa 1870. Muybridge took some of the area’s most iconic images during those formative years of both his own career and the Comstock’s early history.

Travel photographs of this era were commonly converted to stereo cards, which were essentially Victorian-Era virtual reality. The images were doubled and placed side by side on long cardboard strips. The cards would then be placed in wooden stereograph viewer, allowing Victorian audiences to feel as if they were right there in the middle of scenes from interesting and exotic places across the globe, from the comfort of their parlor.

Once flat, still images would now leap off the cardboard stereo card in three glorious dimensions! This 3-D technology was a precursor to the moving picture technology Muybridge would later go on to help pioneer in the late 1870s.

Here is Muybridge’s stereo card image of the Belcher Mine’s hoisting works in Virginia City:

And here is Muybridge’s capture of Devil’s Gate in nearby Silver City, Nevada:

And Muybridge’s portrait of Chang Woo Gow (nee Zhan Shichai), a Chinese vaudevillian entertainer who performed with Barnum & Bailey’s 'Greatest Show on Earth', taken during his visit to Virginia City on August 31, 1870:

Setting the Stage

An overview of Virginia City’s film history would be remiss without noting the region’s rich theatrical and entertainment history. That’s a subject worth studying of its own, but for the sake of context, in brief: Virginia City and Gold Hill’s theaters were among the premiere theatrical establishments in the American West in the 1860s and 1870s.

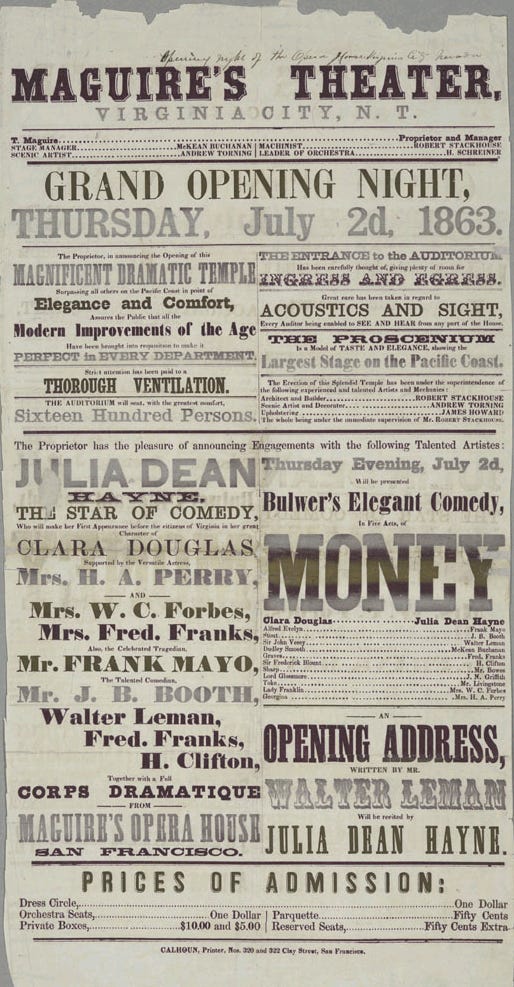

The various opera houses and theaters of the Comstock, from Maguire’s to Piper’s & beyond, welcomed to their footlights the likes of:

Edwin Booth - Renowned Shakespearean actor. Brother of the infamous actor and bad actor John Wilkes Booth. Member of the Booth family acting dynasty—like the Baldwins of their day but with less controversy. Oh, wait…

Lillie Langtree - Socialite, stage starlet, producer, and the mistress of the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII).

Maude Adams - Best known for her theatrical portrayals of Peter Pan. Her performances at Piper’s Opera House in Virginia City later inspired the film Somewhere In Time (1980), starring Christopher Reeve and Jane Seymour. (We’ll explore this in a future installment of this series).

Adah Issacs Menken - “The Menken’s” rendition of a near-nude Mazeppa at Piper’s Opera House in Virginia City in the 1860s is still firmly planted in the pages of Comstock History lore as an oft-repeated tale. Her performances were so well-received on the Comstock she was presented with an embossed silver ingot and a mine was named in her honor (the Mazeppa Mine). She was also the paramour of Alexandre Dumas, the author of “The Count of Monte Cristo” and Camille.

Artemus Ward - Considered the father of stand-up comedy, Ward’s one-night stint at Maguire’s Opera House in Virginia City on D Street turned into a several-week showcase by popular demand.

A pre-fame Mark Twain—as a cub reporter for Virginia City’s iconic Territorial Enterprise newspaper—was in the audience on the first night of Ward’s routine in Virginia City, and lore says he interjected himself into Ward’s act from his seat in “Reporters’ Row”.

Twain’s heckling didn’t get him booted from the theater, instead, it served as an unconventional introduction to Ward and the pair became fast friends. In Ward’s reminiscences of his tour of the West, he recalls raising Cain with Twain around Virginia City and Nevada Territory during his short but influential time performing in the area.

Historians point out that Mark Twain adopted his signature push-broom mustache and unkempt hairstyle—as well as upped the ante on his increasingly irreverent sense humor—only after becoming friends with Artemus Ward.Madame Helena Modjeska - Helena Modjeska was a famous actress in Poland when she immigrated to the United States. But her fame did not precede here when she arrived in the States and she essentially had to start from scratch upon arrival—and learn to speak English at the same time. But she was a quick study and within a year of moving to the States, she was performing starring roles in Shakespearean classics in San Francisco.

The first performances on her first American tour were in Virginia City and Gold Hill. She intentionally chose to perform “Camille” by Alexandre Dumas (remember him from above, as “The Menken’s” paramour?). “Camille”, the beautifully heart-wrenching tale of a beloved prostitute strucken by tuberculosis, was later the basis for the film Moulin Rouge. Modjeska says the miners of the area responded to this tale and her performance as the titular Camille and the rough and rowdy crowd were brought to tears and a standing ovation by the play’s curtain call.

In her masterful memoir, Memories And Impressions Of Helena Modjeska, Mme. Modjeska writes a delightfully entertaining reminiscence of her performances in and visit to Virginia City. A memorable tale includes a humorous retelling of an underground tour of a major mine she undertook, led by Samuel Post Davis (a prominent Virginia City reporter and later editor of the Virginia Chronicle) and the owner of the mine. Though Mme. Modjeska does not name the mine or it’s handsome owner, research indicates it was likely the reportedly raffish & charming “Bonanza King”, James G. Fair).

Even David Belasco, the legendary theatrical producer of Broadway, cut his teeth at Piper’s Opera House in Virginia City before rising to international acclaim in New York City. His namesake can still be found on Broadway today by way of the Belasco Theatre, but his origins began on Virginia City’s own version of Broadway: D Street.

Of course, many more talents traveled to Virginia City and the immediate vicinity to grace the stages of their opera houses. But this short list of acting and producing talents who traveled to and performed in Virginia City, albiet incomplete, helps us set the stage for the silver mining town’s place on the Silver Screen in the decades to follow.

The (Not-So) Silent Film Years

Fast forward to the 1920s, and Virginia City’s once-booming metropolis in the Nevada mountains is now in slow-motion in terms of economics and population. The first elevator west of the Mississippi at the International Hotel on Virginia City’s C Street, Alexander Graham Bell’s installation of early telephones in town and Thomas Edison’s electrifying visits are now novelties of near-distant memory.

Gold and silver was struck in abundance in Missoula, Bodie, Goldfield, the Klondike, and elsewhere since the “Big Bonanza” began to peter out in the late 1870s. The town’s once-robust population was largely lured away from the area by the very thing that led them to Washoe in the first place: the lure of silver and gold.

The prospect of golder pastures didn’t tempt every Comstocker. The town still had a population of 1,200 people, according to the 1920s Census. And those 1,200 folks still needed entertainment.

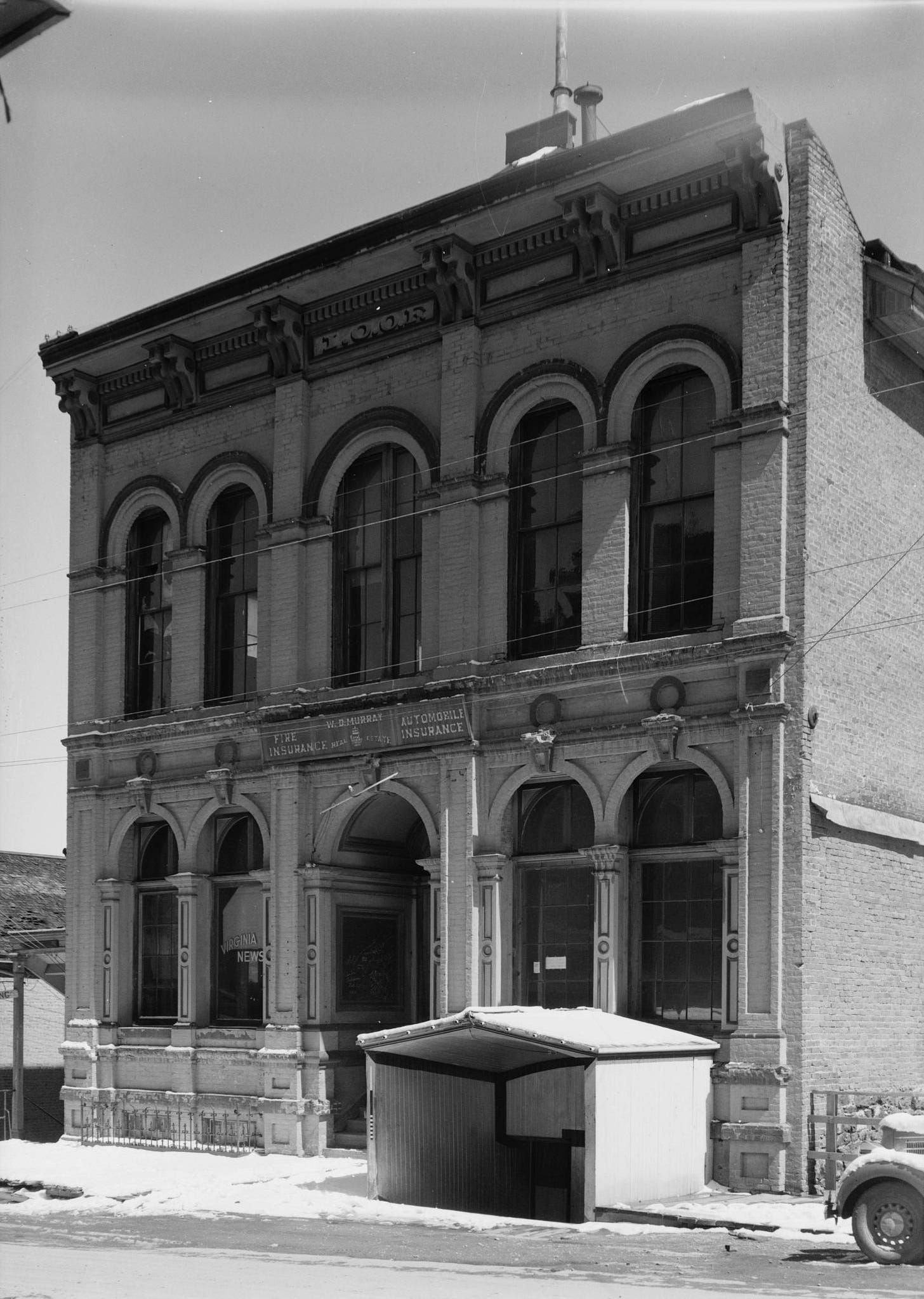

Piper’s Opera House—by then relocated to it’s present day place on B Street—may not have drawn as many A List artists it did in the 1860s and 1870s, some fifty years prior, but it continued to serve as the town’s premiere entertainment hub.

Piper’s of the 1920s served as a communal gathering space for ceremonious occasions such as school graduations, visiting traveling entertainers, and even as a roller rink. (Piper’s serves as a civic crown jewel gathering space in Virginia City to this day, hosting concerts, plays, community meetings, weddings, comedy shows and the annual Nevada Statehood Ball. No longer a roller rink, alas.)

Dan Connors is recalled as “one of the most interesting characters I ever knew" by Ty Cobb, the locally legendary newsman who grew up in Virginia City, Nevada, and attended majestic the Fourth Ward School, which still stands today—now as a Comstock history museum—on C Street in Virginia City*.

Dan Connors was a retired “bare-knuckled prizefighter, manager of a world lightweight champion (Frank Erne), boxing instructor, [and] a ring reporter for New York newspapers,” according to Ty Cobb.** Dan Connors also managed a vaudeville troupe and eventually became the manager “of Piper’s Opera House, where he brought the first movies to Nevada,” according to Cobb.

Ty Cobb grew up on A Street in Virginia City (in the lavishly restored 1876 three-story mansion, now known as the Cobb Mansion Bed & Breakfast) next door to Dan Connors and his family. The Connors’ two-story 1876 manse is one street above and cattycorner from the south-west to Piper’s Opera House. Today, it is painted in a matching color scheme to the Opera House.

Dan Connors married Lavinia Berry, a widow of Edward Piper, the brother of the eponymous John Piper, of Piper’s Opera House footlight fame. “Dan Connors had performed in vaudeville, and managed a traveling company of entertainers,” Ty Cobb wrote in a July 1, 1987 newspaper column. “And his brother ran a concession at New York’s Coney Island. Through these connections, Dan obtained one of the newfangled motion-picture machines and brought to Virginia City the first movies.”

“This was before the days of sound, of course,” Ty Cobb continues in his subsequent column of July 8, 1987, “and Dan projected the silents on a big screen in Piper’s Opera House.”

Dan Connors may have brought the first silent films to Virginia City, but they weren’t actually silent, Cobb said. “The movies were silent, yes, but Connors provided appropriate sound to go with the film,” Cobb recalled in this article.

In other silent film era movie houses, it was customary to have musicians play live music to accompany the film in the theater. (Virginia City’s own modern-day local legend Squeek Steele—a Guiness World Record-holding pianist—occasionally lends her talents to silent film showings around the Comstock.)

But Connors went one step beyond, and added in-house foley sound effects to the silent films he screened at Piper’s in the 1920s.

“[Dan Connors] had a kind of machine, wood and canvas, with openings,” says Eddie Connors, the son of Dan Connors (a fellow Fourth Ward School alumn and nextdoor neighbor of Ty Cobb) in Cobb’s article. “And when you turned the crank fast, it sounded like a heavy wind. This was used to add realism to movies of windstorms, typhoons, etc.”

Dan Connors is said to have hidden his early, not-so-silent film special effects behind the screen at Piper’s Opera House. He “also had a contraption, behind the screen, a collection of pieces of tin, iron and glass,” recalled Ty Cobb. “At the appropriate time, two boys would tip over the box and pour out all of the stuff, creating a tremendous crash.”

This caucophany of make-shift foley effects from behind the projection screen at Piper’s was used at opportune moments to mimic the sounds of “train wrecks and other catastrophes of the screen—so vivildy and loudly that people in the audience screamed in alarm,” Ty Cobb recalled.

“There was a comedy involving chickens, like some thieves raiding a chicken coop,” Eddie Connors said in the same article. “Dad had several chickens behind the movie screen and at the right time, the kids would disturb them so they started clucking loudly. It sounded real.”

There are few historical records readily available today to review the names or types of films shown at Piper’s Opera House in the 1920s or 1930s, and Ty Cobb accounts for this. “There was no theatre marquee to advise citizens of the films to be shown,” Ty Cobb writes. “But I recall there was a large round board containing many light globes, hung just above one of the front doors, and when we’d see that all lit up, we rejoiced to know there was a movie coming up.”

When Ty Cobb penned these reminiscences in 1987 about a slice of his childhood growing up in Virginia City, this illuminated round board was no longer lit or hung outside Piper’s Opera House.

However, this iconic light beacon has since been restored and reinstalled, and today, it illuminates to all curious onlookers that Piper’s Opera House or its Old Corner Bar is open for entertainment of a variety of styles—not just movies.

Approaching his 70th birthday, Dan Connors retired from his retirement gig as manager of Piper’s Opera House and shuttered the iconic entertainment landmark in the late 1920s, according to Cobb.

“Fearing a fire in the venerable Piper’s,” Cobb wrote, “Dan Connors padlocked the building where Lola Montez and Maude Adams once strutted on the sloping stage, where the great Caruso sang, and where Ada Mencken [sic] rode her horse to ‘eternity’.”

Epilogue

But the show must go on, as the old saw says. Virginia City’s live entertainment and civic gatherings moved elsewhere, and so did the movies. Cobb recalls much of what once occurred in Piper’s, such as dances and sporting events (especially basketball games—Virginia City’s athletic pride and glory), went on to be held at the National Guard Hall on C Street. “The movies were seen there at Cole’s Theater, in the same building,” Cobb said.

But the padlocks on the doors of Piper’s Opera House didn’t prevent Hollywood from attempting to re-enter its hallowed halls on occasion. “One day, hearing a commotion [next door], my mother said, ‘You better go over to Connors’ house; I think he’s in trouble,” Cobb wrote.

“The trouble belonged not to Connors but to two pushy characters from Hollywood,” Cobb said. He recalled the pair wanted to go inside the shuttered Opera House and “became obnoxious when denied entry. It developed into a shoving affair—which then errupted.”

“When I got there,” Cobb wrote, “one fellow was on the bottom step holding his bleeding nose, and the other was draped halfway over the railing [of Connors’ house], dazed.”

Cobb goes on to recall a far more amicable and reverent Hollywood visit to Piper’s Opera House from a famous comedian and “Cowboy Philosopher” of the era, but we’ll explore that story—and other famous figures of Hollywood’s gilded age’s visits to Virginia City—in the next episode.

A cliffhanger?! Yep—it’s one of film’s most famous devices, and I’m not above using it. Check back soon for the next installment of Virginia City’s Film History saga.

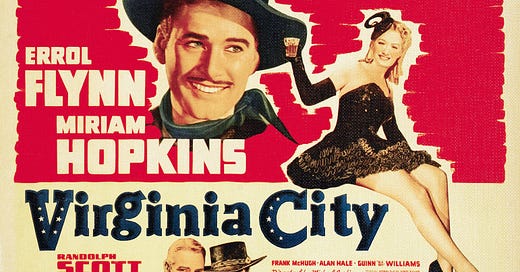

We’ll explore the next chapter of where film history and Virginia City’s history intertwine: the “Talkies” era, the “Golden Age” of the Silver Screen, and Virginia City’s visiting movie stars, from Ronald Reagan to Marilyn Monroe!

Subscribe for free to be notified when Episode Two publishes.

Paid subscribers get to read the next installment right away!

*Your humble scribe is partially employed at the Historic Fourth Ward School Museum in Virginia City, NV — (a fact shared in the interest of full disclosure).

** (Virginia City’s Ty Cobb was named after the famous Detroit Tigers baseball player. No known relation, beyond admiration).